NB. Part of this post is imported from my Medium post, which was written on Dec 1, 2017 during SOCML. It did not cover Day 2. I am slowly collecting my scattered writings from across the web over here, so I decided to go down memory lane a little bit and re-tell my SOCML experience in full.

For those who are new to SOCML, it has been happening since 2016. It is a 2 day event organised by Ian Goodfellow and co. The 2017 edition happened just before NeurIPS, and was located more-or-less on the way, as did the 2018 edition. This positioning in time and space worked really well in 2017. It was a really friendly event, with attendees from all walks of ML — industry, academia, startups, and students. It also covered varying degrees of ML experience, from leaders in the field to those just breaking in to ML. Everyone was available and willing to discuss.

The conference sessions (hour long group discussions) were crowdsourced from amongst the attendees beforehand. I participated in a few. Below are some of my personal musings around these. They do not necessarily fully reflect the points discussed during each session nor do they accurately cover the opinions of others.

Day 1

Interpretability (morning)

The crux of the matter here is to understand why a model does what it does when asked or potentially decides for itself that it has to do something. In my personal opinion, this is a particularly ill-posed problem.

Let’s take for instance human, unless the reader is not one, brains. Our decisions/actions are driven by feelings, which one can interpret as motivation or goals. These can be both short or long sighted. You feel strongly about something, thereby create a goal for yourself. In parts of the world where you have time to think — I luckily live in Norway, and I do — the goals tend to be long sighted.

Every such goal drives one’s behaviour. This should imply that a behaviour can be explained by goals. But, there is a problem here. It is possible to arrive at the same goal state via different paths, each requiring potentially different behaviours driven by various sub-goals. Furthermore, behaviours tend to overlap across different goals.

So, simply looking at the goals is not enough to understand behaviour, even if the goal gets achieved — disregarding asking the achiever to explain their behaviour in natural language, which potentially adds further variation to this understanding. Perhaps then, one has to probe the brain during the act. I do not think we have a good way of doing this with human brains, thereby making the problem ill-posed. But, we do have a better handle on the machine learning models we build, because we build them, thereby letting us probe them e.g. probing individual artificial neurons for what activates them.

Following the dance between goals and catching models in their act makes the problem less ill-posed, and brings fair motivation to working on the problem of interpretability.

Transfer learning/Domain adaptation/Few-shot learning (early afternoon)

My jet lag was kicking in at this point. But, it turns out that researchers working within these domains need a naming convention. Aside from that, learning reusable skills does not hurt, unless old skills become useless. Furthermore, it also makes sense to continuously learn new skills which either augment old skills or are completely novel, while making sure reusable skills aren’t forgotten. By the way, this is a common sense description, and thus I expect researchers driving the field to stay calm and not worry about what I mean by skill in a mathematical sense.

Exploration in RL (late afternoon)

The jet lag was in full bloom by now, but I followed this discussion better than the others, since my day job involves all things RL.

Clever realisations of common sense ideas like novelty, surprise, curiosity, safety, use of/guidance from old knowledge/skills, etc. have enthused this research. All these and more areas were touched upon.

The discussion revolved around a couple of very interesting questions posed by the moderator of our discussion group, Milan Cvitkovic:

Is reward or indeed related ideas of intrinsic/extrinsic motivation all that we have to drive research on exploration? Shaping the reward signal to guide exploration is indeed a heavily explored arena with RL. See what I did there? What could be good ways/metrics for evaluating exploration techniques? How does one technique differ from another? Perhaps visualising policies as they evolve and skills as they get discovered will help. How the distributions of returns for actions evolve, say compared to those resulting using baseline policies e.g. from human demonstrations, may also help. The idea here would be that an efficient exploration technique may deliver policies with return distributions similar to baseline distributions faster (compared to a less efficient one), provided human demonstrations are good baselines of course.

Day 2

ML in Production (morning)

This session was moderated by Omoju Miller from Github. Attendees included folk from H2O.ai, LinkedIn, Adobe, ETH Zurich, etc. Here is a related post from Omoju.

Bringing research to production was one of the concerns we touched upon. Keeping up with ML research is a challenge, and people have different strategies to tackle this, e.g. reading groups, meetups, http://www.gitxiv.com/ etc. But keeping up is one thing. An applied researcher also builds on the latest research and puts it in production, when appropriate. However, one often works in a sandbox, using a bunch of tools — for the sake of exploration — that may not fully sync with the production system in place. In this context, ways to transfer work to production could mean employing data engineers to set up the requisite pipelines for using/testing the trained models. This is costly. There are cheaper alternatives like what H2O.ai makes available, converting models to Java objects, letting one compile these objects in production (assuming a Java production environment). Note that things don’t really get to this stage if data access issues are overlooked.

We also looked at the question of whether there ought to be a separation between research and production people/teams. For a company with money, the answer seems affirmative. On the other hand, in small teams, one usually builds and ships whole products, so having specialist roles may be premature. If indeed there is a separation, a strong technical solution for coherence across teams seems like a natural thing to have.

In general, the groundwork of bringing the latest research to production is still under way across organisations of different sizes. We are in the ad-hoc stage of this endeavour, and best practices are in the works. It did seem reasonable for all applied ML people to aim at making whole products out of their projects/papers, e.g. serve their work through APIs, with an eye out for best practices. This way of work can also be helpful when trying to convince for uptake of your work in the wider organisation.

ML in the Sciences (early afternoon)

Note that before each set of sessions, Ian asked for a show of hands for interest. There was some interest in this session, but when the moment arrived, only two players remained — Kalai Ramea from PARC (the moderator) and myself (the notetaker). This was just as well, as we discovered our mutual interest in agent based modeling (ABM).

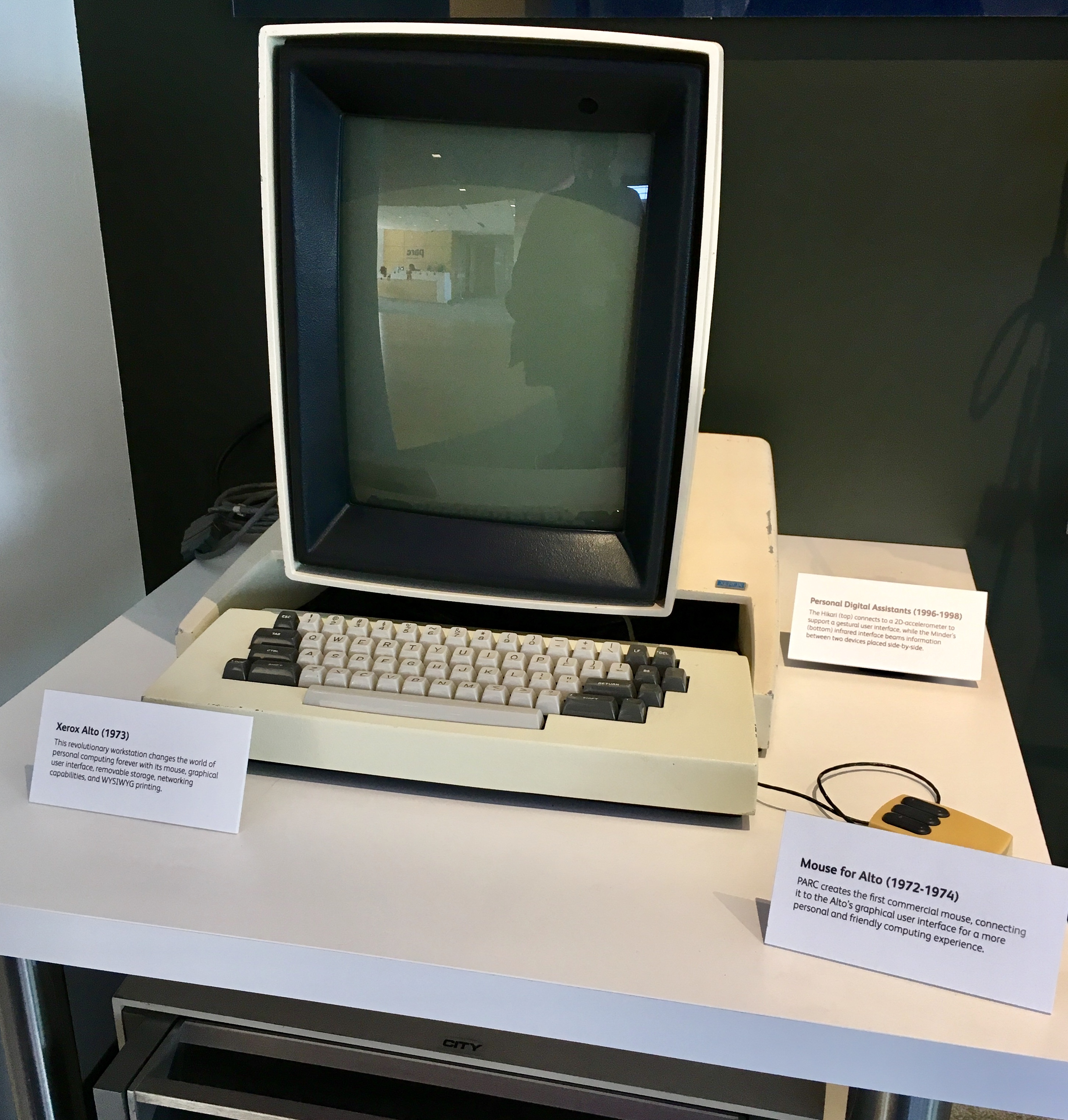

I also got to visit PARC not long after, where we continued discussions on ABM. Just as an aside, I was quite visibly star struck walking the halls of this historic building, thinking about the personal computing and networking pioneers who created our present world in the 70s right there.

Me a little star struck.

The Alto.

Hardware for ML (late afternoon)

Hardware has had a tremendous role in deep learning going mainstream. We are at a time when AI researchers and practitioners cannot just keep an eye on new developments in this space, but acively try to design algorithims that can scale with compute1, whether or not one has access to new hardware. One should be aware of the different architectural possibilities out there — from incumbents like NVIDIA, and to the extent possible, from promising challengers like Graphcore. We are also at a stage where architectures can be influenced by generic algorithmic advances. The co-evolution of AI hardware and algorithms/workloads has only just begun.

The chief scientist of NVIDIA was present in this discussion, which meant that questions gravitated quite a bit in Bill’s direction. A bunch of topics were discussed. One of them was if the world needed different hardware for training vs. inference. The notion of specialised hardware for inference on the edge and cloud does not seem extremely far fetched, but time will tell. Further specialised ASICs for inference in the low power regimen, e.g. for IoT functions, also seemed reasonable. Feasibility of neuromorphic architectures to break into the market was met with some skepticism. Technical (CUDA related) and access frustrations with GPUs could also be felt.

Furthermore…

Apart from these sessions, there were some excellent posters, many of which involved GANs, and at least one involved wormholes to past/future memories.

Kalai also had a fantastic poster about transferring intricate styles on to silhouettes at the conference. Check out this git repo and get your styles transferred!

Last but not least, I got introduced to a nice tool for turning git repos into interactive Jupyter notebooks, called binder. Here is a related research paper.

All in all, I had a great time, and I hope to return to SOCML again in the near future.

-

Given a dataset, model, and an epoch budget, throwing more compute resources for training should lead to a decrease in wall time. This decrease has practical limits, due to the communication overhead resulting from the movement of data, model parameters, and gradients, over training iterations. An algorithm, or more specifically training workload, that can scale with compute is one which manages to balance compute and communication well enough for communication to cause minimal overhead (e.g. by masking it with computation, compressing gradients, etc.), without any reduction in the performance of the trained model. Maintaining performance has implications for more fundamental changes to the optimisation machinery. These ideas also apply to solving problems with bigger and richer models that require more memory than available on single accelerators. ↩